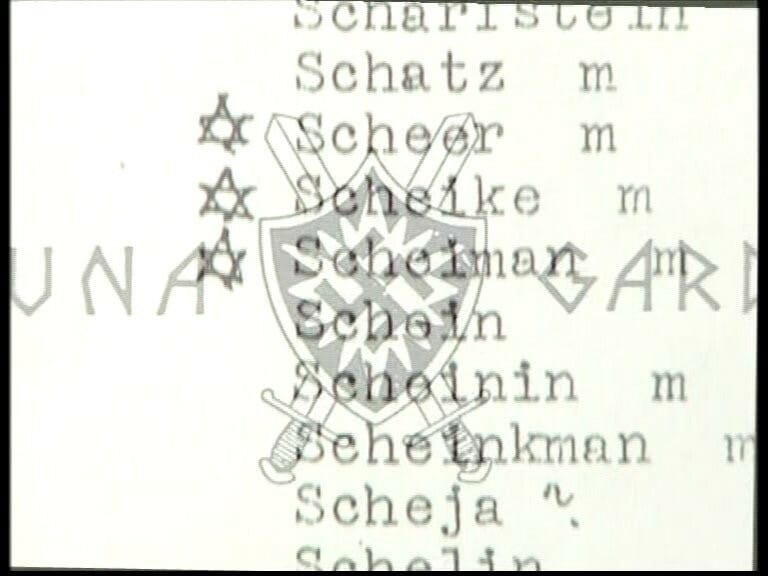

The attached photo below is said to be a list of names from an inventory work carried out in Sweden about 80 years ago, during the 2nd World War. When you discover your own surname in such a list, it all becomes very close and personal. Sweden was never invaded in the end, but had the wings of history fluttered a little bit differently in the middle of the last century, I might not have existed. The genetic code of my ancestors could have played a decisive role in the decision whether or not my family lineage should be eliminated. It had nothing to do with religion, the decisions were only based on a political strategy in times of war.

I am writing this for a reason, I am paying attention to this today because during my lifetime I have thought about how to relate to this part of our history and finally landed in an mindset that I believe and find comfort in. I´ve landed in an approach to this, a thought, an idea that at first glance may be perceived as provocative, namely:

Do not take it too seriously

I would like to elaborate on this and explain – take it just as respectfully seriously so that you find it valuable to listen how other people think and relate to exclusion, hatred, gender issues, integration issues, migration, diversity, freedom of choice, human rights and integrity.

But do not take it so overly seriously that you become blinded and refuse to invite value-focused conversations. Do not close any opinions, observations or voices outside – let curiosity win over frustration. Do not do as I experience is the dominant approach in media, political or even scientific circles in society today where groups, parties, individuals with ‘wrong’ opinions gets excluded from the discussions.

Disagreements are not dangerous, but polarization is. So do not allow your brain’s reflexive threat reaction force you to flee or treat other people with exclusion, denial, or ridicule, regardless of the positions they represent. Respect each other’s opinions. Listen. For real. Enter the dialogue and start talking, ask questions – even if you do not share the same opinion. Do not be so sure that you are right, and the other person is wrong. There are very few things in life that we can say we know with a hundred percent certainty that “this is the truth”. As a matter of fact, to actually know what is deeply true or false, real or fake is getting more difficult to distinguish between. And these struggles to deeply understand and determine between what is what is not going to be easier in the future.

So let us practice, say the wrong things without being led to believe that it will be devastating, practice cultivating your own opinions, your internal models of ethics and morale and find your inner values by exercising your synapses, your vocabulary, your way to formulate questions and develop your inner thought models by talking to those around you about what’s truly important. Through this labor we´ll build step-by-step together an inclusive society, a society where we treat each other as the sovereign individuals we are and start respecting everyone’s own unique, special abilities instead of treating and determine each other from superficial epithets such as gender, ethnicity, religion, age, health status etc. In short, we will develop social sustainability in practice. Social sustainability is said to be the least developed domain within the context of sustainability (the others being ecological and financial).

If we focus on maturing the social sustainability in our society together we will be able to prevent bad scenarios from our past to repeat itself – makeing sure that similar scenarios as the Holocaust must not be allowed to happen again. It is difficult to approach the Holocaust, difficult to talk about it, difficult to put words that matches how we feel about it when we look at the result – the most horrific thing that could happen.

But – with that being said, I’m convinced that it did not happen overnight but because of an enormous number of small events, coincidences and countless human emotions and micro-decisions that led to the possibility that this scenario could unfold. What I want us to focus on in the future is how we could explore and build a robust social sustainability in society based on networking, openness, respect and courage where we dare to explore ourselves and our behavioral patterns so that we get to the bottom of what the underlying factors existed that could lead humanity so crookedly. For only when we are, really, aware of these factors and mechanisms we can work to prevent them, socially, politically, technologically. How can we on an early-stage measure and detect indicators that we are deviating from our social contracts, such as our fundamental human rights and other ethics principles such as the Nuremberg code?

I work with technical development and testing of digital solutions. I see that in the present day we do not have a clue on how to build robust ethical mechanisms into our solutions, mechanisms that will play a crucial role when we, through digitalization, hope to be able to build a better world. Today, we are getting used to the idea that algorithms help us by recommending the most reasonable choice, so-called recommendation engines. However, it has already been shown that this rather simple form of artificial intelligence is fraught with problems as the algorithms cannot be more intelligent than the data we feed it with. These recommendation algorithms are today built in to support doctors, authorities, staff in all of society’s support systems. But too many observations have already been noted where technology has failed to consider, for example, gender equality, which has resulted in the introduction of the term technochauvinism up on the agenda.

Surveys show that more than 8 out of 10 development companies have already noted unethical effects as a result of the implementation of artificial intelligence, so what more moral/ethical implications are we unaware of in today’s fast-moving race towards digitalization? Doctors who unknowingly plan an operation earlier based on the patient’s gender or ethnicity? Migration decisions based on previously executed decisions, which in turn are based on culture and tradition – ‘this is how we have previously handled matters concerning that region’. If our already existing directives, processes and routines remain based on over-simplistic models and approaches even before digitization, AI will not help. Artificial intelligence is not a magic wand. If we do not first learn for ourselves how to develop self-awareness, self-leadership, ethics and morals and what this means we will act superficially, or even wrongly. These actions are then fed into the shape of data into our digital products, and they will learn and replicate – perhaps even reinforce – our shortcomings.

It is therefore of the utmost importance that we thoroughly explore how we think about ourselves and our values, but at the same time explore how to develop models for how we could ‘educate’ our digital solutions and in the end programming fairness into our systems. Every one of us should investigate and focus on a mature way to learn the craft of understanding data – because it is from this our self-learning digital components will pick insights as well as make decisions from. As a start, we should at least start to discuss technoethics as an obvious term on the development agenda where we investigate issues such as – How do we want our future systems to act and behave? What indicators of injustice will we search for? According to what values, standards or protocol? This journey begins now, but we must begin with ourselves. For the picture I attached to the register for Jews living in Sweden is not bad by itself. There is no unclean, no evil intention in the actual representation of data. It is how the data is used, which decisions are made based on the data that may have moral and ethical implications. Today it may be your doctor, firefighter, politician or tax administrator who still have the executive responsibility for decisions related to your life, but how long will it take before these professionals thinks it is more efficient to let the algorithms in a machine make those decisions instead?

Because, in the not-so-distant future we will let machines make decisions for us. How are we going to ensure that these do not – through a vast number of autonomous small decisions in countless digital systems – slowly but surely on a grander scale deviate from what we thought was obvious, pure and right? I just do not want us to stand there in 80 years’ time and say, ‘How could digitalization lead humanity so wrong’? Is this an imminent risk? Well, since digitalization is merely creating a mimicking digital twin, a lagging shadow representation of our own society – it will become our responsibility to catch this opportunity to build a better version of ourselves, instead of our evil digital twin.

In order to read more I recommend these references to start with:

English | EN

English | EN