THE GREEN FIELD AND SOFTWARE EVOLVABILITY

March 31, 2014

A quick look over this planet will tell you that people like making things. We like to conceive and create new things. Yes, preferably new things. In this overpopulated world with a lot of occupied space and established knowledge, there are often old things standing in the way of creating something new. That can be frustrating because don’t we all think it’s more fun to set the first steps in an untouched white carpet of snow rather than see if we can make something nice out of someone else’s junk?

A quick look over this planet will tell you that people like making things. We like to conceive and create new things. Yes, preferably new things. In this overpopulated world with a lot of occupied space and established knowledge, there are often old things standing in the way of creating something new. That can be frustrating because don’t we all think it’s more fun to set the first steps in an untouched white carpet of snow rather than see if we can make something nice out of someone else’s junk?

Although recycling finally has become daily business in many industries, with its relatively new technologies, IT professionals have had the privilege of being creators-only for quite a while. And like most creators, they usually prefer working on greenfield projects over working on brownfield projects.more–>

That’s how sometimes a case is made to replace (part of) a system, instead of upgrading it: the analyst is of the opinion that it would be better to rewrite the whole program to make it fit today’s functional and technical requirements.

There can be a mismatch between personal beliefs or preferences and the company’s economic best interests here. The old system’s business case probably also once promised a long-term solution, providing added value over the entire length of its life, but when a trusted technical expert says that it would be more economical to replace the system, the business manager is inclined to accept a sunk cost.

It is important to note that the technical expert is not using their expertise in bad faith:

- ICT is still developing rapidly, so software can quickly be labeled “outdated” from a technical point of view.

- It can be hard to predict the effort that will be needed to completely understand the system and the effect of any changes on it, especially when software is badly documented, or not entirely standardized.

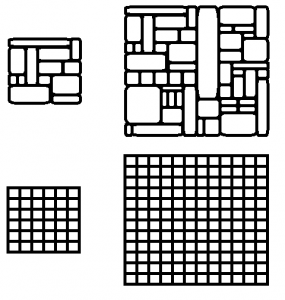

IT projects are often built as greenfield, from-scratch projects. Developers build solutions that fill the need at the moment, but the technological and functional factors in the environment may change, which in turn changes the requirements. When requirements keep changing (and they usually do), computer applications seem to do a bad job “changing” in the long term. What appear to be small changes often require a lot of work throughout the software. This is in contrast with the fact that it is “soft” ware. It is again important to note that this is not the developer’s fault. Even if s/he anticipates certain changes or builds in options for extensions/features – contrary to modern principles like the Minimum Viable Product and You Ain’t Gonna Need It – systems would gain complexity as they are changed until upgrading is no longer justified and a new from-scratch project is started.

So, there is a real problem with software evolvability. And it is a challenge for IT professionals today to work on a solution for it. In my opinion, much of the solution to this problem needs to be achieved in software design. What is needed is a structural solution which does not put pressure on other resources and therefore ought to be independent of the developer herself. Programmers today still make a lot of decisions themselves about the structuring of code. But maybe they shouldn’t. If you rely on developers to implement the right structure, you are putting pressure on a scarce resource: not all companies will be able to attract the finest developers who are at the same time code monkeys, business analysts, quality managers, and architects. Because, yes, we do expect our modern developers to be all that. Following an implemented standard, however, works well for all-round developers, as in developers who are not great architects but prove their value in other aspects. It should even be possible to industrialize and automate parts of the coding process (cf. model driven architecture for example). Another advantage of adhering to a well-documented standard is that code is more likely to be self-explanatory, so less specific documentation needs to be produced.

The software design standard we are looking for should probably show a high degree of service orientation, i.e. consisting of self-contained, loosely coupled units of functionality. Its structure should be sufficiently modular, granular even, to guarantee a proper separation of concerns. The final goal is to arrive at a situation where 1 change in requirements is equal to 1 change in software – whereas we see today that 1 change in some module requires a lot of changes elsewhere.

There are design methods around which are focused on achieving exactly that and which are already more tangible than being mere theories. For example, Sogeti Belgium is involved in an R&D project with the University of Antwerp to put the theory behind normalized systems into practice, and it is getting some promising results. Hopefully, I might be able to write some more about it in a future blog post.

There is a big downside, however, to software design being the solution to the problem of software evolvability: it is so the core of the software that implementing it implies that most of the system would probably need to be rebuilt from scratch. On the other hand, the point of this post was that your software will arrive at that point anyway due to its increasing complexity.

Before implementing a new software design, a necessary first step might be for businesses to reconsider their mindset about software development. Taking “service orientation” to a higher level, businesses should consider moving away from having software delivered as a product, but instead think of the IT department as continuously delivering services which are consistently in line with business needs. This means stop differentiating between a build phase and a maintenance phase for software, but instead come up with KPIs assessing the delivered services throughout the software’s life span, from the moment you start building it.

As a final note: ideally, the solution to the problem of software evolvability does not take away the human pleasure of creating but focuses on taking away the annoying tasks of scanning and refactoring code. Let’s make developing software a process of continuous creation. Impossible? I don’t think so. And what do you think?

English | EN

English | EN