FUNDAMENTALS FOR ARCHITECTURE PRINCIPLES (PART3)

January 18, 2023

In my first blog of this series, I described what architecture principles are and what they should consist of. The second was about how are they created and used in context of decision making. This third and final blog in this series, is about ethics and their relation to architecture principles.

Philosophy and ethics are not your day-to-day topics, especially when you think of a profession that is embedded in a mainly technology driven IT sector. However, we use ethics in our life every day and hour.

Ethics is applying moral values in our daily decision making. Because all enterprise decisions affect people, and because we as architects facilitate good decision making as a profession, we should be aware of moral values and how they steer decision making.

Don’t be afraid of a bit of theory, I will try to make it accessible and practical!

A short introduction to ethics

Decisions are made by everybody all the time, mostly subconsciously. Architects are typically involved when there is deliberate, rational decision making. Supported by our architecture principles. Deliberate, rational decision-making is “expensive” in time and effort, hence in our case it is mainly done on a subset of management or organisation design decisions that have a major impact on the enterprise and its employees. Such as investment decisions, ranking a portfolio, personnel changes, organisation structure development etcetera.

To get a basic understanding of the available way of thinking in ethics, especially normative ethics, here are the four most applied and distinctive approaches. Virtue ethics, deontology, consequentialism and role ethics.

- Virtue ethics philosophers look at the person itself.

Their major questions are: “what should a virtuous person be?”, ”What makes me courageous?”, ”What makes me a wise person?”, ”Am I a righteous or fair person?”.

By looking at your own heart and complying to moral values of your community, a virtuous person makes the right decision. The thinkers associated with virtue ethics are Aristotle, Socrates and Plato. - Philosophers applying the deontological approach evaluate the action after the decision in the light of a fixed set of moral rules, disregarding the consequences. The dominant questions seem to be “am I doing the right thing?” or “how does the intended action compare to my duties?”. The thinkers associated with deontology are Immanuel Kant and William David Ross.

- With the third approach, consequentialism, philosophers take an option, a potential decision, and evaluate all possible consequences. Associated thinkers are Jeremy Bentham, Elizabeth Anscombe and Auguste Comte.

The many variations of this approach ask two different questions.- What consequences? What is the delivered value? (happiness, love, money, state welfare etc).

- Consequences for whom? Who do we deliver this value to? (myself, my family, the state, society, humanity)

These three normative approaches, virtue ethics, deontology, and consequentialism, are all based on Western philosophy.

A much-used Eastern approach is based on the teachings by the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE) and pre-dates all the Western approaches.

Confucius distinguishes virtues at three levels.

- The virtues for the self (the cultivation of knowledge, faithfulness and sincerity);

- the virtues regarding my relation to friends, family, and relations such as employees or my boss (righteousness) and

- the virtues towards others (seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness).

Confucius’ fundamental virtues are means between extremes. Too little is stingy, too much is profligate, the right way (mean) is generous. Too little is insincere, too much is reckless, the right way (mean) is sincere. Knowledge is knowing what is too little or too much and what the mean ought to be. This knowledge is developed by experience, by making mistakes and learning. (Bonevac, 2021)

For visual thinkers

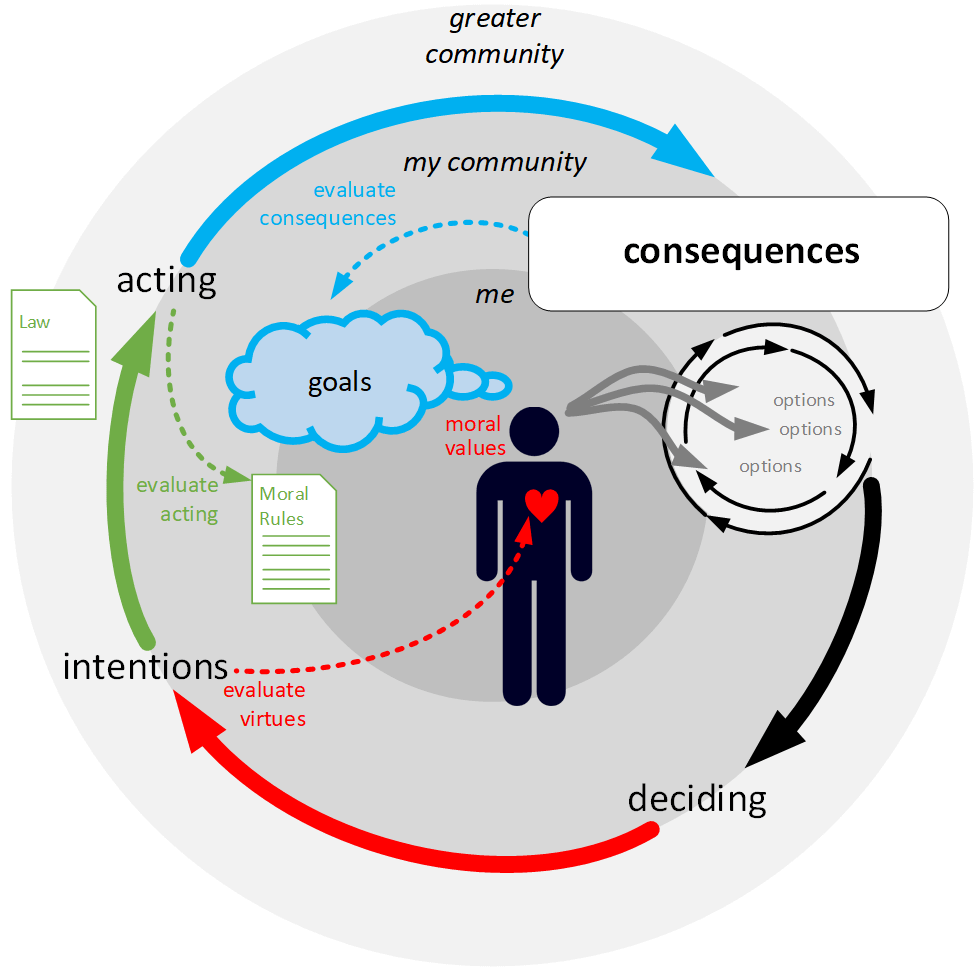

The relation between these approaches had me puzzling for some time. Authors writing about ethics tend to use many words to describe their concepts. So, I created a visualisation that helped me, and potentially you too, to grasp the concepts behind ethical thinking. Do you recognise the single-loop learning process from the second blog?

- Decision-makers applying the virtue ethics approach (red), take the moral values of themselves and evaluate an intention based on the current options.

- Decision-makers applying the Confucian approach (red), take the moral values on three levels (me, my community, and the greater community) and evaluate an intention based on the current options.

- Decision-makers applying the deontological approach (green), take the moral rules of their community and evaluate the intentions and actions based on the current options.

- Decision-makers applying the consequentialist approach (blue), define their community goals and evaluate the consequences that potentially result from the intentions and actions based on the current options.

A practical application

The practical application of the combination of architecture principles and ethics lies in being aware of these approaches. This takes time and needs some examples. These are mine, reasoning about the phase of evaluating and formulating principles.

Limit freedom

From a virtue ethical standpoint, one could argue that creating architecture principles that maximise the facilitation of discussion, promote the autonomy of the employees that apply these principles. Very strict rules that leave no room for any discussion limit freedom for employees. The existence of many architecture principles guides decision making to a detailed level. It will limit freedom too. So, the types and amount of architecture principles that are created are affected by the enterprise virtues that promote freedom and trust in employees and become a part of the enterprise culture framework.

Prescriptive principles

Architecture principles being a prescriptive instrument that guide our decisions and our actions can be seen as a deontological tool. Most examples of architecture principles are explicitly intended to be formulated as disputable and comparable to Kant’s imperfect duties. Enablers of a mature discussion that are not intended as absolute rules. An example taken from cases (Greefhorst and Proper, 2011, table 6.1): “A balance needs to be found between their preferences and the efficiency of the various channels and entry points, on the condition that no-one is excluded.”. Stronger forms, more rule-like implications are “Data will be acquired from the source system.” or “things that must be validated or are required before proceeding” or “people that must be consulted”. Consequences of the actions are not to be considered when a deontological approach “rule is rule” is taken.

Who to include?

The four types of relations by Confucius, a form of role ethics, can be specifically addressed in the formulation of architecture principles, comparable to the stockholder and stakeholder theories. Deciding to create different principles for different stakeholders is a moral question. What stakeholders to include, who to exclude?

Change relations

“A manager may overrule a decision by an employee”. Or “customer is king”, reversing the priority in the skewed relation between employees and Confucius’ strangers. Principles about caring for your customers, being fair and honest despite the difference in the information position between the two parties, indicate the application of benevolence towards those same strangers.

Potential recommendations

Based on my reasoning, I am creating a list of recommendations that may help to improve the quality of architecture principles, and the quality of the process to get to architecture principles. Here is some of them in the context of the process step of formulating, part of the double-loop learning:

- Take note of internal policies, corporate governance guidelines, (national) law and strategy statements and documents. These may contain the rules that the enterprise is guided by. (deontology)

- Be explicit and transparent about the rationales, this links a principle to the enterprise moral values. (a virtue of the writer)

- All the enterprise statements may contain references to relevant stakeholders and their concerns. Do not forget the internal stakeholders such as employees as they are a dominant source of the enterprise values. (role ethics)

- Limit the number of principles, allow for interpretation, do not write strict rules. Delegate the responsibility of interpreting the principles to others. This gives a sense of freedom and ownership of decisions. Essential elements of an enterprise culture. (virtue ethics)

- Do not limit the scope of the consequences to the enterprise only. Respect all human rights, animal rights and the environment. Be inclusive to all stakeholders, direct and indirect. Do not disregard the impact of your enterprise on the society as a whole, now, in a while and in the distant future as if your decisions affect you, your enterprise, your family, and your children. (deontology (Kant), consequentialism, role ethics)

Do you agree on these recommendations?

A challenge for you

I challenge you to think of others. What virtues are applicable when you apply a principle? What rules are there in your organisation when you try to convince your board of directors to confirm your new set of principles? Does this match you personal need of safety and freedom? Do you create a simple principle that is easily understood by a manager and give lots of discussion? Or describe many theoretically and language correct deliberations that are very effective?

This is applied ethics in your daily work as architect!

About

This deep dive in the fundamentals of architecture principles is part of my explorative research with a goal to improve the quality of the principles and their life cycle processes, contributing to improving the organisations we work for.

Because all enterprise decisions affect people, architects should be aware of moral values and how they steer decision making. My premise is that architects implicitly and concurrently use multiple forms of normative ethics when applying architecture principles.

If you are interested in this explorative research that combines the fundaments in learning theory, feedback loops from cybernetics, architecture best practices, and my preliminary understanding of philosophy and ethics, please contact me at Hans.Nouwens@sogeti.com.

References

Bonevac, D. (2021). Confucius’s role ethics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZwI0IbA9TmQ.

Greefhorst, D. and Proper, E. (2011). Architecture principles: the cornerstones of enterprise architecture. The Enterprise engineering series. Springer, Heidelberg; New York. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20279-7.

Mintzberg, H. and Westley, F. (2001). Decision making: It’s not what you think. MIT Sloan Management Review, page 89. OCLC:926162036.

https://store.hbr.org/product/decision-making-it-s-not-what-you-think/SMR067

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/

About Confucius https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confucianism

English | EN

English | EN