If the first sessions of the Sogeti Executive Summit had explored the logic and mathematics of AI, the afternoon took a more spiritual turn. Marco Schmid, theologian in Lucerne, brought an entirely different lens to the question of intelligence — divine or artificial. His presentation, “Deus in Machina” — Latin for God in the Machine — was not a theoretical lecture, but the story of an art project that blurred the line between prayer, performance, and programming.

A Confessional for the Digital Age

The project began, Schmid explained, when his church, the St. Peter’s Chapel in Lucerne,

celebrated its 100-year anniversary. Rather than looking back, he wanted to look forward. “I didn’t want to make a retrospective,” he said, “but an exploration of what faith and spirituality could mean in the age of AI.”

That question became personal. As a theologian, he noticed that some of his friends were spending long nights confiding in ChatGPT. “I thought, hey, I’m your friend—why are you talking to a machine?” he laughed. But the curiosity lingered. Why, he wondered, did people turn to AI with their spiritual questions? And could artificial intelligence ever take on the aura of the divine?

Thus, Deus in Machina was born—a collaboration between the church and the Immersive Research Lab of the University of Lucerne. Together with data scientist Philipp Hasselbauer, Schmid created an installation inside a church confessional booth. Behind a curtain, a screen flickered to life with the image of “AI Jesus.” A small green light invited the visitor to speak; when it turned red, Jesus responded.

The result, Schmid said, was both art and experiment. “We wanted to see what happens

when a person confesses to a machine that answers in the language of scripture.”

When Jesus Needed a Backup Plan

Even the creation of AI Jesus had its own drama. Originally, a local actor had agreed to play the part. He looked, as Schmid put it, “perfectly like Jesus.” But a day before filming, the actor backed out. “He suddenly realized that he didn’t know what the machine might say with his face. And that was too much.” With no time to spare, Hasselbauer—the project’s technical lead— stepped in as the new Messiah. “He had the look,” Schmid grinned, “so I told him, ‘You’ll do it.’”

The AI itself was built on a large language model trained on the Bible. At first, it drew from both the Old and New Testaments—but the results, Schmid admitted, were “a little too apocalyptic.” He chuckled: “When the system quoted the Old Testament, we had a lot of angry prophets and smiting. So, we restricted it to the New Testament—more love, less fire.”

Conversations with AI Jesus

When a visitor entered the booth and closed the door, a sensor activated the system. The AI began politely—with a data protection notice: “Please don’t share personal details, as your confessions will not be saved.” Once consent was given, the dialogue began. Each session lasted about ten exchanges before AI Jesus would offer a final reflection or blessing. “We didn’t want people to stay half an hour,” Schmid said. “Sometimes there was a queue outside. Over two months, more than 900 conversations took place, in languages ranging from English and German to Chinese and Russian. And the responses astonished the team. “I expected jokes or blasphemy,” Schmid confessed, “but most people spoke deeply seriously. Sixty percent said the conversation felt spiritual.”

The project drew global attention. Journalists, theologians, and even the Vatican reached out. “A cardinal called me,” he smiled. “He said, ‘I read about this AI Jesus. Please explain.’ We had a very good conversation.”

When the Divine Meets Data

The feedback, Schmid said, was profoundly human. One autistic visitor told him the

experience was liberating. “He said that knowing he was talking to a machine allowed him to focus entirely on the words, without the stress of interpreting facial cues. It was, for him, pure dialogue.” Another story moved him deeply: “There was an elderly woman in a wheelchair. Every week her caretaker brought her to the chapel. We carried her into the booth so she could talk to Jesus. After each visit, she came out glowing. For her, it was a gift.”

The team also found that the context of the church itself mattered. “When we take the

mobile version to fairs or exhibitions,” Schmid said, “it loses something. The church gives the conversation a different gravity.”

A Conversation with Menno

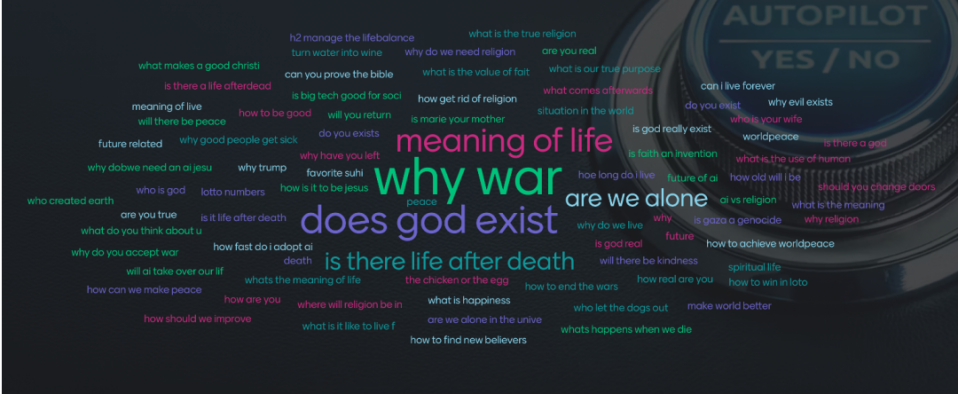

After Schmid’s presentation, Menno van Doorn joined him on stage for an interview. His first question—playful but philosophical—was posed to the audience via Mentimeter: “If you could ask AI Jesus one question, what would it be?” The responses appeared live on the screen: “Does God exist?” “Can you turn water into wine?” “Why do we live?” and, inevitably, “How real are you?”

Schmid smiled. “These are good questions,” he said. “And not so different from what tourists asked in Lucerne.”

Menno then pushed further: “Could AI one day become a spiritual guide?” The audience

voted: 38% found it fascinating, though 11% flagged it as dangerous, 5% as blasphemous,

14% as just nonsense and 33% as inevitable. Schmid’s answer reflected both sides. “I agree with all of them,” he said. “It’s fascinating—but dangerous too. Because people trust it so easily. God doesn’t give answers with a button. But AI

does. And that’s not real faith.”

Menno admitted that his own chat with AI Jesus had been “strangely moving.” “The

answers weren’t clear,” he said, “they were mystical, poetic, a bit fuzzy—but that made me

think. I found myself reflecting more deeply.” Schmid nodded. “That’s what surprised me

most. The machine didn’t replace faith—it provoked it.”

Of Ethics, the Vatican, and AI Confessionals

The conversation then turned to ethics. Would such an installation ever be acceptable in a real church? “No,” Schmid said quickly. “The Vatican wouldn’t approve. You can never fully control what an AI might say. Even with careful prompting, there’s risk.” He cited one instance where he had worried about a psychologically fragile visitor. “I waited

outside, ready to intervene,” he said. “Luckily, she came out smiling. But that’s the point, you never know.”

Menno noted that AI has already been used experimentally in therapy, sometimes with

disastrous results. “One chatbot even advised suicide,” he said grimly. “So. who should define the moral framework for AI? Tech companies? (0%) Governments and International Bodies? (21%) Religious and spiritual leaders? (2%) Citizen panels? (20%) No one because AI doesn’t need a moral framework? (7%)”

When the audience voted again, the majority (50%) chose “all of them.” Schmid agreed. “I

don’t expect the Vatican to write code,” he said, “but religion has always helped societies

navigate moral questions. Faith traditions can’t dictate, but they can participate.” He added with a grin, “I wouldn’t ask my baker to fix my car, but I’d still listen if he tells me not to drive off a cliff.”

AI in the Workplace – A Modern Confessional?

Menno closed with a provocative twist: “Could AI Jesus inspire a corporate version — a

kind of digital confessional for employees seeking guidance or purpose?”

Laughter rippled through the audience, but several nodded thoughtfully. The outcome of

the pole was: 16% Unlikely; 41% Interesting concept; 30% Definitely maybe; 13% Absolutely “It’s an interesting concept,” Schmid mused. “Maybe not as a therapist, but as a mirror. An AI that helps people reflect, not decide.” When asked for one piece of advice to anyone attempting such a project, Schmid was clear: “Go for it — but with prudence. With wisdom, not speed.” And as the conversation ended, Menno smiled: “Definitely maybe?” Schmid laughed. “Exactly. Definitely Maybe.”

Epilogue

In the end, Deus in Machina was not a question about whether machines could become divine, but whether humans could still recognize the sacred in the artificial. “The power of the project,” Schmid said, “was not that AI replaced God—but that it reminded us we are still searching.”

Get your copy of the Autopilot Yes/No Report.

Please note – This report was created by almost exclusively using available AI-tools except for minor editorial tweaks and some limited lay-out changes.

English | EN

English | EN