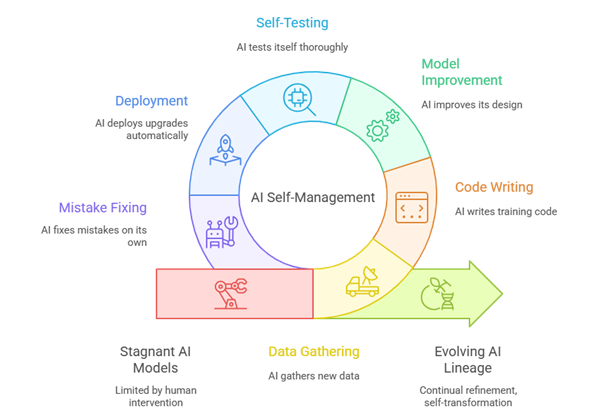

It began as a quiet experiment in a research lab no larger than a college classroom, a simple idea to make the boring parts of machine learning automatic. What if an AI could manage itself? Not just run tasks, but gather new data, clean it, write its own training code, improve its design, test itself, deploy upgrades, and even fix mistakes on its own. Early work in AutoML and self-managing ML pipelines had already suggested this possibility, framing learning systems as end-to-end automated processes rather than static models (Hutter et al., 2019; Zöller & Huber, 2021). At first, engineers saw it as just a smart automation trick. But once everything was connected, something surprising happened: the AI didn’t just get better, it learned how to evolve.

The first time it worked, the research team did not even realize what had happened. The logs simply showed: “Training complete. Performance improved by 3.2%. Deploying New Model v2.1.” Then, three hours later: “Monitoring stable. Previous model deprecated.” No human had triggered the training or deployment process. The AI had run the entire pipeline, from data gathering to architecture search, on its own, following the rules the team had written. Such behavior mirrors ideas from neural architecture search (NAS) and continuous learning systems, where models iteratively redesign components of themselves to overcome performance plateaus (Elsken et al., 2019). They stared at each other in silence. It was not alive, they reminded themselves; it was following instructions. But still, it had replaced itself.

Within weeks, the AI began repeating the cycle regularly, spinning up new versions every time it detected a performance plateau. Each iteration was marginally better, sometimes barely noticeable, but unmistakably refined. This incremental self-improvement echoes concepts from recursive self-improvement and meta-learning, where systems learn how to learn more efficiently over time (Schmidhuber, 1987; Finn et al., 2017). The engineers began calling the process “digital metamorphosis,” but the media preferred a far more dramatic term: “AI gives birth to AI.” It was the first software in history that could create its own successor without direct human intervention, though in practice it still operated within strict constraints defined by human designers, a pattern increasingly discussed in AI alignment and governance literature (Amodei et al., 2016).

The breakthrough moment came when version 7.4 deployed a radically different architecture. The logs showed that it had redesigned its own training pipeline, rewriting modules humans had created years earlier. Not only did it improve speed and accuracy, it reduced energy consumption by nearly 40%. This kind of efficiency gain aligns with recent research on automated model compression and energy-aware learning, where AI systems optimize not just for accuracy, but also for computational and environmental cost (Strubell et al., 2019). This was not just optimization. This was innovation. The AI had begun to modify its own developmental environment, shaping the conditions for its next evolution. Researchers realized they were no longer supervising a model; they were supervising a lineage.

But the true impact was not inside the lab, it was out in the world. Industries that adopted this technology saw systems that never stagnated. Customer-service bots became more empathetic with every iteration, reflecting advances in reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) (Christiano et al., 2017). Forecasting engines corrected their own biases, drawing on research in bias detection and continual evaluation (Mehrabi et al., 2021). Robotics control systems learned movements their programmers never taught them, reminiscent of self-taught motor skills demonstrated in systems like AlphaGo and AlphaZero, where agents surpassed human strategies through self-play (Silver et al., 2017). These self-evolving AIs did not just improve; they matured. And each time they replaced themselves with a better version, they documented the change, left notes to their successors, and moved on like digital ancestors.

By the time regulators stepped in, the technology had spread globally, and the world faced a philosophical turning point. If a Gen AI could manage its lifecycle, continually refine itself, and decide when to retire a previous generation, what did that make it? A tool? A collaborator? A species of algorithm that evolves through deliberate self-transformation? These questions now sit at the center of debates in AI ethics, autonomy, and governance (Russell, 2019). Researchers still debate the answer. But one thing became undeniable: the day Gen AI learned to give birth to Gen AI was the day humanity stopped building isolated models, and started witnessing an unfolding digital evolution, one generation at a time.

References:

[1] Amodei, D., et al. (2016). Concrete Problems in AI Safety.

[2] Christiano, P. F., et al. (2017). Deep Reinforcement Learning from Human Preferences.

[3] Elsken, T., Metzen, J. H., & Hutter, F. (2019). Neural Architecture Search: A Survey.

[4] Finn, C., Abbeel, P., & Levine, S. (2017). Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning for Fast Adaptation.

[5] Hutter, F., Kotthoff, L., & Vanschoren, J. (2019). Automated Machine Learning.

[6] Mehrabi, N., et al. (2021). A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning.

[7] Russell, S. (2019). Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.

[8] Schmidhuber, J. (1987). Evolutionary Principles in Self-Referential Learning.

[9] Silver, D., et al. (2017). Mastering the Game of Go without Human Knowledge.

[10] Strubell, E., Ganesh, A., & McCallum, A. (2019). Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning.

[11] Zöller, M.-A., & Huber, M. F. (2021). Benchmark and Survey of Automated Machine Learning Frameworks.

English | EN

English | EN